EVM, Solidity, and Vyper

How to use the slides - Full screen (new tab)

EVM, Solidity, and Vyper

EVM

Ethereum Virtual Machine

A VM designed specifically for the constraints and features of Ethereum

EVM Properties

- Deterministic: execution outcome easy to agree upon

- Spam-resistant: CPU and other resources are metered at a very granular level

- Turing-complete (with a caveat)

- Stack-based design

- Ethereum-specific (EVM can query block hash, accounts and balances, etc.)

Notes:

It is critical that the EVM be 100% deterministic and that each implementation produce the same outcome. Even the smallest discrepancy between two running nodes would lead to different block hashes, violating consensus about the results.

History of Ethereum

- Nov 2013: Vitalik released WP

- Apr 2014: Gav released YP

- July 2014: $18M raised (ICO lasted 42 days)

- July 2015: Frontier released -- bare bones, Proof of Work

- Sept 2015: Frontier "thawed", difficulty bomb introduced

- July 2016: DAO Fork

- 2016-2019: Optimizations, opcode cost tuning, difficulty bomb delays

- 2020: Staking contract deployed, Beacon Chain launched

- 2021: EIP-1559, prep for The Merge

- 2022: The Merge (Proof of Stake)

- 2023: Staking withdraw support

---v

DAO Hack

- 2016: raised $150M worth of ETH

- Later that year: 3.6M ETH drained

- Reentrancy attack

- "Mainnet" Ethereum forks to retroactively undo hack

- Ethereum Classic: code is law

Notes:

A DAO ("Decentralized Autonomous Organization") is much like a business entity run by code rather than by humans. Like any other business entity, it has assets and can carry out operations, but its legal status is unclear.

The earliest DAO ("The DAO") on Ethereum suffered a catastrophic hack due to a bug in its code. The DAO community disagreed on whether or not to hard-fork and revert the hack, resulting in Ethereum splitting into two different chains.

---v

The first smart contracting platform

Ethereum has faced many challenges as the pioneer of smart contracts.

- Performance: Underpriced opcodes have been attacked as a spam or DoS vector

- High gas fees: Overwhelming demand low block-space supply

- Frontrunning: Inserting transactions before, after, or in place of others in order to economically benefit

- Hacks: Many hacks have exploited smart contract vulnerabilities

- Problems with aggregating smart contract protocols together

- Storage bloat: Misaligned incentives with burden of storage

---v

Idiosyncrasies

- Everything is 256bits

- No floating point arithmetic

- Revert

- Reentrancy

- Exponential memory expansion cost

Gas

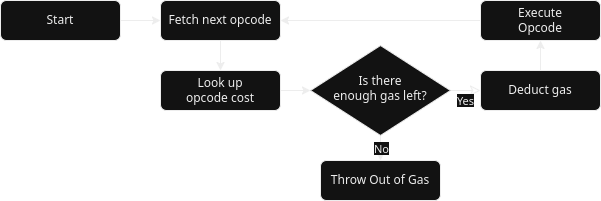

Turing completeness and the Halting Problem

-

EVM: Turing-complete instruction set

-

But what about the Halting Problem?

-

Obviously cannot allow infinite loops

-

Solution: Gasometer, a way to pre-pay for each opcode execution

Notes:

The Halting Problem tells us that it's not possible to know that an arbitrary program will properly stop. To prevent such abuse, we check that there is gas remaining before every single opcode execution. Since gas is limited, this ensures that no EVM execution will run forever and that all work performed is properly paid for.

---v

Gasometer

- Checks before each opcode to make sure gas can be paid

- Safe: prevents unpaid work from being done

- Deterministic: results are unambiguous

- Very inefficient: lots of branching and extra work

Notes:

This not only makes it possible to prevent abuse, but crucially allows nodes to agree on doing so. A centralized service could easily impose a time limit, but decentralized nodes wouldn't be able to agree on the outcome of such a limit (or trust each other).

---v

Gas limits and prices

Gas: unit of account for EVM execution resources.

gas_limit: specifies the maximum amount of gas a txn can paygas_price: specifies the exact price a txn will pay per gas

A txn must be able to pay gas_limit * gas_price in order to be valid.

Notes:

This amount is initially deducted from the txn's sender account and any remaining gas is refunded after the txn has executed.

---v

EIP-1559

An improvement to gas pricing mechanism.

gas_price --> max_base_fee_per_gas

\-> max_priority_fee_per_gas

- Separates tip from gas price

base_feeis an algorithmic gas price, this is exactly what is paid and is burned- ...plus maybe tip if (

base_fee < max_base_fee + max_priority_fee) - Algorithmic, congestion-based multiplier controls

base_fee

Notes:

https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-1559 Introduced in London hard-fork.

---v

OOG and Gas Estimation

If a txn exhausts its gas_limit without finishing, it will produce an OOG (out-of-gas) error and all changes made in the EVM are reverted (except for fee payment).

In order to estimate the amount of gas a txn will need, an RPC method (eth_estimateGas) can perform a dry-run of the txn and record the amount used.

However, there are a few caveats:

- Run against current state (state may change)

- The RPC node could lie to you

- This is expensive infrastructure overhead and can be a spam vector

Account Types

There are two types of Ethereum accounts. Both use 160-bit account IDs and can hold and send Ether, but they are controlled very differently.

---v

Account Types

Externally-owned Account (EOA)

- Traditional user-controlled account

- Controlled via private keys

- Account ID generated by hashing public key

- Uses an incrementing nonce to prevent replay attacks

Contract Account

- Controlled by immutable bytecode

- May only ever do precisely what the code specifies

- Account ID generated deterministically when bytecode is deployed

Transactions

A transaction is a signed payload from an EoA which contains details about what the transaction should do and how it will pay for itself.

---v

Transactions fields:

- value: 0 or more Ether to send with the txn

- to: the target of this transaction

- input: Optional input data for creating or calling a contract

- gas_limit: Max gas the txn will pay

- gas_price: (or EIP-1559 equivalent)

- nonce: prevents replay attacks and forces ordering

- signature: proves ownership of private keys, allows receiving Account ID

- there can be more

---v

Possible use-cases:

- Call a contract's external function (

inputspecifies function and arguments) - Create a contract (

inputspecifies contract's bytecode) - Neither (

inputempty)

In all cases, Ether can be sent (Neither being a normal Ether send).

---v

Transaction Validity

Before executing (or gossiping) txns, some validity checks should be run:

- Is the

gas_limitsufficient? (21_000minimum at least pays for processing) - Is the signature valid? (Side effect: public key recovered)

- Can the account pay for

gas_limit * gas_price? - Is this a valid (and reasonable) nonce for the account?

Notes:

These checks come with overhead, so it's important to discard invalid txns as quickly as possible if it is invalid. This includes not gossiping it to peers, who have to also verify it.

Opcodes and Bytecode

An opcode is a single byte which represents an instruction for the VM to execute.

The EVM executes bytecode one opcode at a time until it is done, explicitly halts, or the gasometer runs out of gas.

Notes:

Functions compile down into a sequence of opcodes, which we call bytecode. This bytecode is bundled together and becomes the on-chain contract code.

ABI

ABI ("Application Binary Interface") describes the bytecode for a contract by annotating where functions and other objects exist and how they are formatted.

---v

Exercise

Review this Contract Code on Etherscan

---v

Sandboxed Contract State

Contract Accounts contain a sandboxed state, which stores everything that the

contract writes to storage.

Contracts may not write to storage outside of their own sandbox, but they can call other contracts whose bytecode might write to their respective storage.

---v

Calling Contracts

Contract functions can be invoked in two ways different ways:

- EoAs can call a contract functions directly

- Contracts can call other contracts (called "messaging")

---v

Types of contract messaging

- Normal

call: Another contract is called and can change its own state staticcall: A "safe" way to call another contract with no state changesdelegatecall: A way to call another contract but modify our state instead

Notes:

Transactions are the only means through which state changes happen.

---v

Message Object

Within the context of a contract call, we always have the msg object, which lets us know how we were called.

msg.data (bytes): complete calldata (input data) of call

msg.gas (uint256): available gas

msg.sender (address): sender of the current message

msg.sig (bytes4) first 4 bytes of calldata (function signature)

msg.value (uint256) amount of Ether sent with this call

---v

Ether Denominations

Ether is stored and operated on through integer math.

In order to avoid the complication of decimal math, it's stored as a very small integer: Wei.

1 Ether = 1_000_000_000_000_000_000 Wei (10^18)

Notes:

Integer math with such insignificant units mostly avoids truncation issues and makes it easy to agree on outcomes.

---v

Named Denominations

Other denominations have been officially named, but aren't as often used:

wei = 1 wei

kwei (babbage) = 1_000 wei

mwei (lovelace) = 1_000_000 wei

gwei (shannon) = 1_000_000_000 wei

microether (szabo) = 1_000_000_000_000 wei

milliether (finney) = 1_000_000_000_000_000 wei

ether = 1_000_000_000_000_000_000 wei

gwei is often used when talking about gas.

Programming the EVM

The EVM is ultimately programmed by creating bytecode. While it is possible to write bytecode by hand or through low-level assembly language, it is much more practical to use a higher-level language. We will look at two in particular:

- Solidity

- Vyper

Solidity

- Designed for EVM

- Similar to C++, Java, etc.

- Includes inheritance (including MI)

- Criticized for being difficult to reason about security

---v

Basics

// 'contract' is analogous to 'class' in other OO languages

contract Foo {

// the member variables of a contract are stored on-chain

public uint bar;

constructor(uint value) {

bar = value;

}

}

---v

Functions

contract Foo {

function doSomething() public returns (bool) {

return true;

}

}

---v

Modifiers

A special function that can be run as a precondition for other functions

contract Foo {

address deployer;

constructor() {

deployer = msg.sender;

}

// ensures that only the contract deployer can call a given function

modifier onlyDeployer {

require(msg.sender == deployer);

_; // the original function is inserted here

}

function doSomeAdminThing() public onlyDeployer() {

// this function can only be called if onlyDeployer() passes

}

}

Notes:

Although Modifiers can be an elegant way to require preconditions, they can do entirely arbitrary things, and auditing code requires carefully reading them.

---v

Payable

contract Foo {

uint256 received;

// this function can be called with value (Ether) given to it.

// in this simple example, the contract would never do anything with

// the Ether (effectively meaning it would be lost), but it will faithfully

// track the amount paid to it

function deposit() public payable {

received += msg.value;

}

}

Notes:

The actual payment accounting is handled by the EVM automatically, we don't need to update our own account balance.

---v

Types: "Value" Types

contract Foo {

// Value types are stored in-place in memory and require

// a full copy during assignment.

function valueTypes() public {

bool b = false;

// signed and unsigned ints

int32 i = -1;

int256 i2 = -10000;

uint8 u1 = 255;

uint16 u2 = 10000;

uint256 u3 = 99999999999999;

// fixed length byte sequence (from 1 to 32 bytes)

// many bitwise operators can be performed on these

bytes1 oneByte = 0x01;

// address represents a 20-byte Ethereum address

address a = 0x1010101010101010101010101010101010101010;

uint256 balance = a.balance;

// also: Enums

// each variable is an independent copy

int x = 1;

int y = x;

y = 2;

require(x == 1);

require(y == 2);

}

}

---v

Types: "Reference" Types

contract Foo {

mapping(uint => uint) forLater;

// Reference types are stored as a reference to some other location.

// Only their reference must be copied during assignment.

function referenceTypes() public {

// arrays

uint8[3] memory arr = [1, 2, 3];

// mapping: can only be initialized from state variables

mapping(uint => uint) storage balances = forLater;

balances[0] = 500;

// dynamic length strings

string memory foo = "<3 Solidity";

// also: Structs

// Two or more variables can share a reference, so be careful!

uint8[3] memory arr2 = arr;

arr2[0] = 42;

require(arr2[0] == 42);

require(arr[0] == 42); // arr and arr2 are the same thing, so mod to one affects the other

}

}

---v

Data Location

Data Location refers to the storage of Reference Types.

As these are passed by reference, it effectively dictates where this reference points to.

It can be one of 3 places:

- memory: Stored only in memory; cannot outlive a given external function call

- storage: Stored in the contract's permanent on-chain storage

- calldata: read-only data, using this can avoid copies

---v

Data Location Sample

contract DataLocationSample {

struct Foo {

int i;

}

Foo storedFoo;

// Data Location specifiers affect function arguments and return values...

function test(Foo memory val) public returns (Foo memory) {

// ...and also variables within a function

Foo memory copy = val;

// storage variables must be assigned before use.

Foo storage fooFromStorage = storedFoo;

fooFromStorage.i = 1;

require(storedFoo.i == 1, "writes to storage variables affect storage");

// memory variables can be initialized from storage variables

// (but not the other way around)

copy = fooFromStorage;

// but they are an independent copy

copy.i = 2;

require(copy.i == 2);

require(storedFoo.i == 1, "writes to memory variables cannot affect storage");

return fooFromStorage;

}

}

---v

Enums

contract Foo {

enum Suite {

Hearts,

Diamonds,

Clubs,

Spades

}

function getHeartsSuite() public returns (Suite) {

Suite hearts = Suite.Hearts;

return hearts;

}

}

---v

Structs

contract Foo {

struct Ballot {

uint32 index;

string name;

}

function makeSomeBallot() public returns (Ballot memory) {

Ballot memory ballot;

ballot.index = 1;

ballot.name = "John Doe";

return ballot;

}

}

Solidity Hands-On

---v

Dev Environment

We will use the online Remix IDE for our sample coding. It provides an editor, compiler, EVM, and debugger all within the browser, making it trivial to get started.

---v

Flipper Example

Code along and explain as you go

---v

Exercise: Multiplier

- Write a contract which has a

uint256storage value - Write function(s) to multiply it with a user-specified value

- Interact with it: can you force an overflow?

Overflow checks have been added to Solidity. You can disable these by specifying an older compiler. Add this to the very top of your

.solfile:pragma solidity ^0.7.0;

---v

Bonus:

- Prevent your multiplier function from overflowing

- Rewrite this prevention as a

modifier noOverflow()

The constant

constant public MAX_INT_HEX = 0xffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff;may be helpful.

Vyper

- Also designed for the EVM

- Similar to Python

- Intentionally lacks some features such as inheritance

- Auditable: "Simplicity for the reader is more important than simplicity for the writer"

---v

Compared to Solidity

Vyper mostly lacks features found in Solidity, all in the spirit of improving readability. Some examples:

- No Inheritance

- No modifiers

- No function overloading

- No recursive calling (!)

- No infinite-loops

---v

Basics

# There is no `contract` keyword.

# Like Python Modules, a contract is implicitly

# scoped by the file in which it is found.

# storage variables are declared outside of any function

bar: uint

# init is used to deploy a contract and initialize its state

@external

def __init__(val):

self.bar = val

---v

Functions

@external

def doSomething() -> bool:

return True

---v

Decorators and Payable

# Vyper contains decorators for restricting functions:

@external # function can only be called externally

@internal # function can only be called within current context

@pure # cannot read state or environment vars

@view # cannot alter contract state

@payable # function may receive Ether

# also, to cover the most common use case for Solidity's modifiers:

@nonreentrant(<unique_key>) # prevents reentrancy for given id

Notes:

source: https://docs.vyperlang.org/en/stable/control-structures.html#decorators-reference

---v

Types

# value types are small and/or fixed size and are copied

@external

def valueTypes():

b: bool = False

# signed and unsigned ints

i: int128 = -1

i2: int256 = -10000

u: uint128 = 42

u2: uint256 = 42

# fixed-point (base-10) decimal values with 10 decimal points of precision

# this has the advantage that literals can be precisely expressed

f: decimal = 0.1 + 0.3 + 0.6

assert f == 1.0, "decimal literals are precise!"

# address type for 20-byte Ethereum addresses

a: address = 0x1010101010101010101010101010101010101010

b = a.balance

# fixed size byte arrays

selector: bytes4 = 0x12345678

# bounded byte arrays

bytes: Bytes[123] = b"\x01"

# dynamic-length, fixed-bounds strings

name: String[16] = "Vyper"

# reference types are potentially large and/or dynamically sized.

# they are copied-by-reference

@external

def referenceTypes():

# fixed size list.

# It can also be multidimensional.

# all elements must be initialized

list: int128[4] = [1, 2, 3, -4]

# bounded, dynamic-size array.

# these have a max size but initialize to empty

dynArray: DynArray[int128, 3]

dynArray.append(1)

dynArray.append(5)

val: int128 = dynArray.pop() # == 5

map: HashMap[int128, int128]

map[0] = 0

map[1] = 10

map[2] = 20

---v

Enums

enum Suite {

Hearts,

Diamonds,

Clubs,

Spades

}

# "hearts" would be considered a value type

hearts: Suite = Suite.Hearts

---v

Structs

struct Ballot:

index: uint256

name: string

# "someBallot" would be considered a reference type

someBallot: Ballot = Ballot({index: 1, name: "John Doe"})

name: string = someBallot.name

Vyper Hands-On

---v

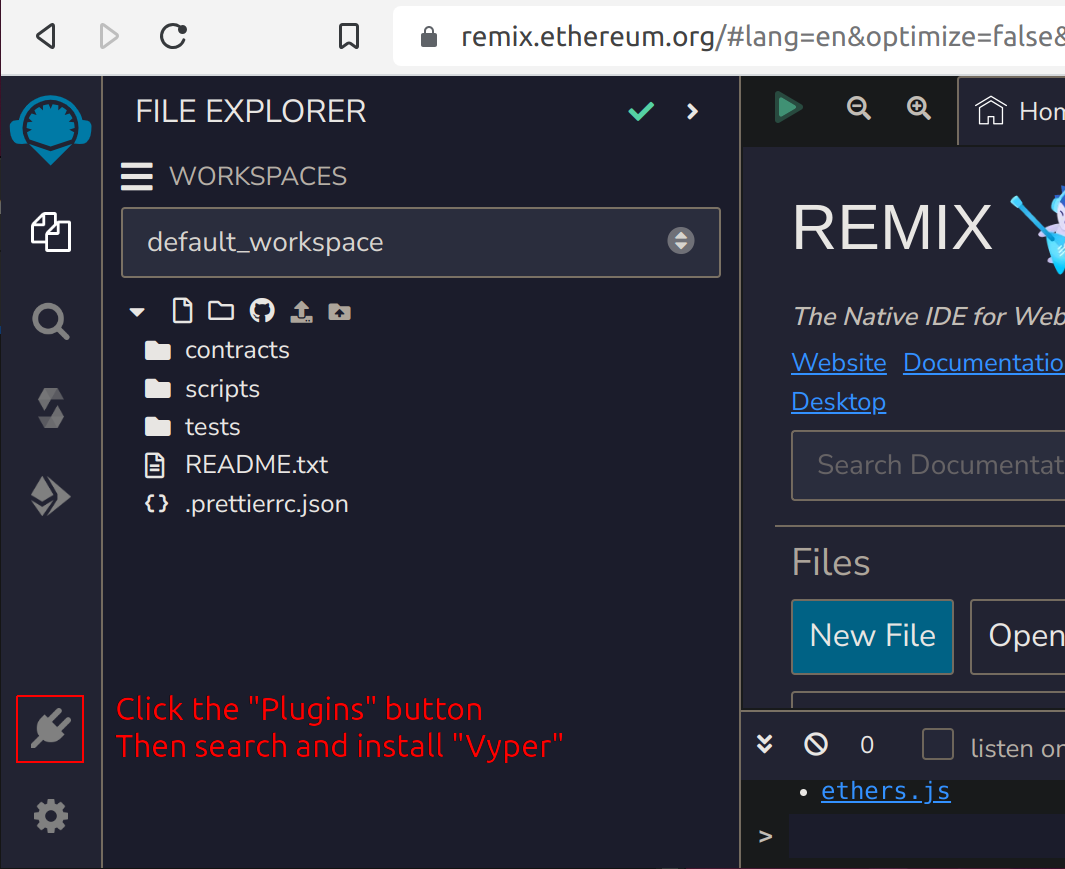

Remix Plugin

Remix supports Vyper through a plugin, which can be easily enabled from within the IDE. First, search for "Vyper" in the plugins tab:

---v

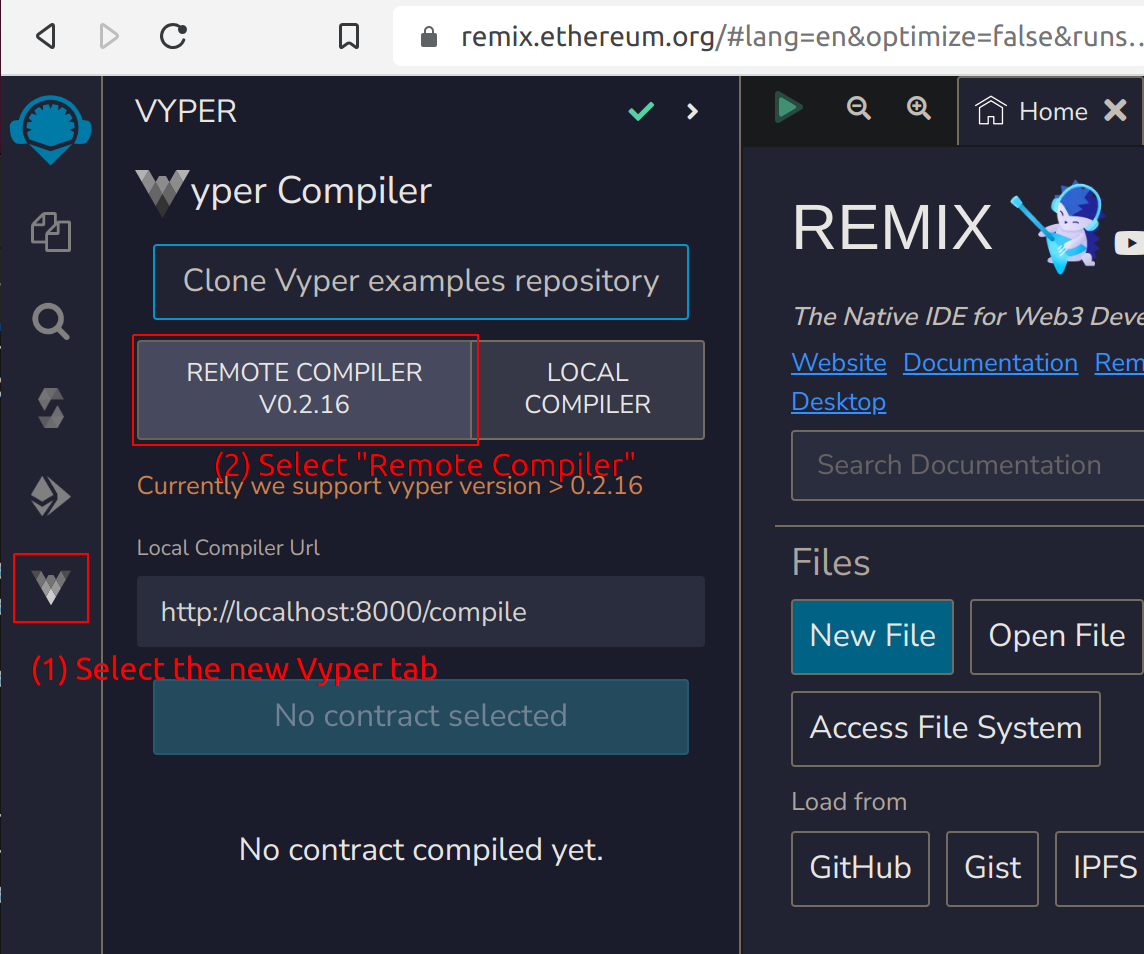

Remix Plugin

Use Vyper through the new Vyper tab and use "Remote Compiler"

Reentrancy

The DAO Vulnerability

function withdraw() public {

// Check user's balance

require(

balances[msg.sender] >= 1 ether,

"Insufficient funds.

Cannot withdraw"

);

uint256 bal = balances[msg.sender];

// Withdraw user's balance

(bool sent, ) = msg.sender.call{value: bal}("");

require(sent, "Failed to withdraw sender's balance");

// Update user's balance.

balances[msg.sender] = 0;

}

We make a call to withdraw user's balance before updating our internal state.

---v

How can this be avoided?

- Commit state BEFORE contract call

- Modifier that prevents reentrancy (Solidity)

@nonreentrantdecorator (Vyper)

Storing Secrets On-Chain

Can we store secrets on-chain?

What if we want to password-protect a particular contract call?

Obviously we can't store any plaintext secrets on-chain, as doing so reveals them.

---v

Storing Hashed Secrets On-Chain

What about storing the hash of a password on chain and using this to verify some user-input?

Accepting a pre-hash also reveals the secret. This reveal may occur in a txn before it is executed and settled, allowing someone to frontrun it.

---v

Verifying with commit-reveal

One potential solution is a commit-reveal scheme where we hash our reveal with some salt, then later reveal it.

// stored on-chain:

secret_hash = hash(secret)

// first txn, this must execute and settle on chain before the final reveal.

// this associates a user with the soon-to-be-revealed secret

commitment = hash(salt, alleged_secret)

// final reveal, this must not be made public until commitment is recorded

reveal = alleged_secret, salt

verify(alleged_secret == secret)

verify(commitment == hash(salt, alleged_secret))

---v

Alternative: Signature

Another approach is to use public-key cryptography. We can store the public key of some key pair and then demand a signature from the corresponding private-key.

This can be expanded with multisig schemes and similar.

How does this differ from the commit-reveal scheme?

Notes:

Commit-reveal requires that a specific secret be revealed at some point for verification. A signature scheme provides a lot more flexibility for keeping the secret(s) secure.