Game Theory Basics

How to use the slides - Full screen (new tab)

Game Theory Basics

Notes:

Game theory is a field of study at the intersection of mathematics and economics. It consider an economic system to be a game and people to be players. According to the rules of the game, it analyzes the players' best strategies and then uses this analysis to explain the observed behavior of the economic system.

Game theory is an interesting an powerful tool, because it's fairly simple and intuitive, yet extremely powerful to make predictions. Hence, it's a good idea to learn game theoretical principles and keep them in the back of your mind when designing economic systems.

Outline

- Lesson

- What is Game Theory?

- What is a Game?

- Types of Games

- Common Games

- Nash Equilibrium

- Equilibrium Selection

- Workshop & Activities

- Discussions & more games

What is Game Theory?

Game theory studies strategic situations where the outcome for each participant or 'player' depends on the actions of all others. It formulates models to represent these scenarios and predicts the most likely or optimal outcomes.

Notes:

- Game theory is all about the power of incentives.

- Helps you understand and design systems and guide behavior of participants.

Game Theory in Web3

In the context of blockchains, game theoretic reasoning is used for modelling and understanding.

Notes:

- The term is heavily over-used.

- 9/10 times people using the term they simply mean there is some economic structure behind their protocols.

- Rarely real game theoretic analysis is done.

Modelling

- Tokenomics: Macroeconomic design of a token (inflation, utility, etc.).

- Business Logic: Interaction of the token with different modules of a protocol.

- Consensus: Providing sufficient incentives to guarantee that participating nodes agree on a distributed state of the network.

- Collaboration: Nudging (aggregated) human behavior and their interaction with the protocol.

Understanding

- Economics: Interaction between different protocols and how finite resources are allocated among all of them.

- Security: Testing economic security of protocols against various types of attacks.

History of Game Theory

- Early “game theoretic” considerations going back to ancient times.

- “Game theoretic” research early 19th century, still relevant.

- The systematic study of games with mathematically and logically sound frameworks started in the 20th century.

- Modern game theory is used in economics, biology, sociology, political science, psychology, among others.

- In economics, game theory is used to analyze many different strategic situations like auctions, industrial economics, and business administration.

Notes:

- In Plato's texts, Socrates recalls the following considerations of a commentator of the Battle of Delium:

- An example is a soldier considering his options in battle: if his side is likely to win, his personal contribution might not be essential, but he risks injury or death. If his side is likely to lose, his risk of injury or death increases, and his contribution becomes pointless.

- This reasoning might suggest the soldier is better off fleeing, regardless of the likely outcome of the battle.

- If all soldiers think this way, the battle is certain to be lost.

- The soldiers' anticipation of each other's reasoning can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy: they might panic and retreat before the enemy even engages, resulting in a defeat.

- Spanish conqueror Cortez, when landing in Mexico with a small force who had good reason to fear their capacity to repel attack from the far more numerous Aztecs, removed the risk that his troops might think their way into a retreat by burning the ships on which they had landed

- Antoine Augustin Cournot, a french mathematician, already described a duopoly game with respective solution in 1844.

- We will see this later.

- Examples:

- Biology: Animals fight for resources or are peaceful, why cooperation evolved

- Political science: Art of conflict, escalation and de-escalation between nations.

Game theory is abstract

- Game theoretic models aim to get at the essence of a given strategic problem.

- This often requires many simplifying assumptions.

- Pro: Abstraction makes the problem amenable to analysis and helps to identify the key incentives at work.

- Con: A certain lack of realism.

- In any case: Modeling a strategic situation always entails a tradeoff between tractability and realism.

Notes:

- Need to explain what we mean by lack of realism:

- Often people have more choices than we model.

- Often people take other things into consideration when making choices than the model allows.

- Often people know more/less than we assume.

- How to resolve the tradeoff between tractability and realism is often subjective and depends on the taste of the modeler.

What is a Game?

Definition: (Economic) Game

- A game is a strategic interaction among several players, that defines common knowledge about the following properties:

- all the possible actions of the players

- all the possible outcomes

- how each combination of actions affects the outcome

- how the players value the different outcomes

Definition: Common Knowledge

- An event $X$ is common knowledge if:

- everyone knows $X$,

- everyone knows that everyone knows $X$,

- everyone knows that everyone knows that everyone knows $X$,

- ... and so on ad infinitum.

Examples: Common Knowledge

Auctions

- Actions: Bids.

- Outcome: Winner and Payment.

Price-competition

between firms

- Actions: Price charged.

- Outcome: Demand for each firm, profit of each firm.

Notes:

Crucial feature of a game: outcome not only depends on own actions but also on the actions of the other players.

Types of games

Game theory distinguishes between:

- static & dynamic games

- complete & incomplete information games

Static and Dynamic Games

| Static Game | Dynamic Game | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | All players take their actions at the same time | Players move sequentially and possibly multiple times, (at least partially) observing previous actions |

| Simple Example | Rock-Paper-Scissors | Tic-Tac-Toe |

| Economic Example | Sealed-bid auction. | All bidders submit their bids simultaneously (in a sealed envelope). |

| English auction. | Auctioneer publicly raises price if at least one bidder accepts the price. | |

| Representation | Payoff Matrix | Decision Tree |

Notes:

- Also referred to as simultaneous or sequential games

Completeness of Information in Games

| Game of Complete Information | Game of Incomplete Information | |

|---|---|---|

| Information available | All information relevant to decision-making is known. | Not all information relevant to decision-making is known. |

| Simple Example | Chess | Poker |

| Economic Example | Sealed auction for seized Bitcoin. | Used-car market: the resale value of a used car is opaque. |

Notes:

- There is also the notion of perfect and imperfect information which we should skip here. More info: https://economics.stackexchange.com/questions/13292/imperfect-vs-incomplete-information

Quiz

Three firms want to hire an engineer...

- The engineer brings added value to each firm of 300,000 USD per year.

- The payoff of the firm is known by everyone to be 300,000 USD minus the salary.

- The payoff to the engineer is salary minus cost of working, which is known to everyone.

- All firms make a salary offer at the same time.

Quiz Questions:

- Is this game static or dynamic? What would need to change in the description of the game such that it would fall in the other category?

- Is this game of complete or incomplete information? What would need to change in the description of the game such that it would fall in the other category?

Notes:

-

The game is static. For it to be dynamic, firms would need to make offers sequentially, knowing what the firms before had offered.

-

The game is of complete information. To make information incomplete, we would need to have that the value of hiring the engineer differs between firms and is unknown between firms. Or that the cost of working for the engineer is not known to the firms. The point is that we need to have uncertainty over payoffs.

- This lesson focuses on static games of complete information.

- When we look at auctions in lesson Price finding mechanisms, we will also consider games of incomplete information, both dynamic and static.

Utility

- Core concept of Game Theory.

- Can transform any outcome to some value that is comparable.

- For example: What is better? Scenario A: Going for a vacation to France and drink Wine, or Scenario B: going to Germany and drink Beer?

- Those dimensions are only comparable if we give both some value like U(A) = 5, U(B) = 3.

- Essential assumption: Agents are utility maximizers.

- Monetary payouts can also be transformed to utility.

- Simplest assumption U(x) = x.

- But that is likely not true in reality.

- Most things have diminishing rates of returns.

Notes:

- Expected Utility is the average utility we get from comparing several outcomes and weigh them with the probability they occur.

- In the following, we won't need that, because either we deal with money or other dimensions that are comparable.

Common Games

Prisoners' Dilemma

A fundamental problem:

Even though everyone knows there is a socially optimal course of actions, no one will take it because they are rational utility maximizers.

It's a static game of complete information.

Notes:

One of the most famous games studied in game theory.

- Static because both players take their action at the same time.

- Complete because everybody is aware of all the payouts.

Bonnie and Clyde

Bonnie and Clyde are accused of robbing two banks:

- The evidence for the first robbery is overwhelming and will certainly lead to a conviction with two years of jail.

- The evidence for the second robbery is not sufficient and they will be convicted only if at least one of them confesses to it.

Bonnie and Clyde

In the interrogation they both are offered the following:

- If you both confess you both go to jail for 4 years.

- If you do not confess but your partner does, you go to jail for 5 years: 1 extra year for obstruction of justice.

- However, if you confess but your partner does not, we reduce your jail time to one year.

Notes:

They are interrogated in different rooms, apart from each other.

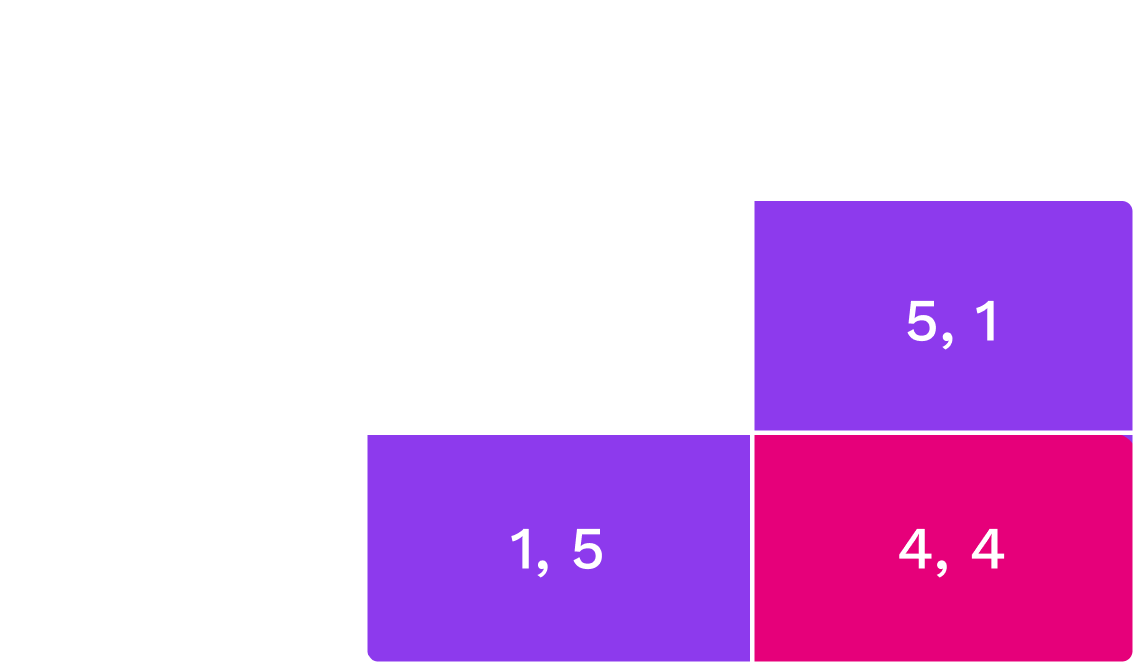

Bonnie and Clyde

- Cooperate ($C$) with each other and not say anything

- Defect ($D$) and confess their crime

Notes:

- They can either cooperate or defect

- First payoff is Clyde, second is Bonnie

Bonnie and Clyde

Choosing D is a dominant strategy: a strategy that is always optimal for a player, regardless of what the other players do.

Notes:

No matter what Clyde does, D is always the best choice. So, they end up both defecting, resulting in 4 years each. It would be in their best interest to cooperate and not to say anything. This would minimize the total jail time for the two. However, both Bonnie and Clyde are rational utility maximizers. So, they end up in a situation where they not only fare worse individually (4 instead of 2) but also jointly (the total jail time is 8 years rather than 4 years).

Nash-Equilibrium

- Fundamental concept in Game Theory

- A NE is a set of strategies, one for each player, such that no player can unilaterally improve their outcome by changing their strategy, assuming that the other player's strategy remains the same.

- In the Prisoner's Dilemma, D/D is the only NE.

Prisoners' Dilemma IRL

- Nuclear Arms Race: NATO and Russia prefer no arms race to an arms race. Yet, having some arms is preferable to having no arms, irrespective of whether the other one is armed.

- OPEC: Limiting oil supply is in the best interest of all. However, given the high price that thus results, everyone has an incentive to increase individual oil supply to maximize profits.

Notes:

OPEC: Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. It is something like a cartel that agree on limiting the global oil production and keep the oil price artificially high.

OPEC and Cartels generally seems to overcome the Prisoners' Dilemma... More on that later.

Ultimatum Game

- We played it before.

- Sequential game.

- The Nash Equilibrium can be reasoned by backwards induction.

- The proposer has the following considerations:

- What would the recipient accept?

- Answer: every payoff (larger than 0).

- Therefore, I should offer, since I want to maximize my payout, something equal or slightly higher than 0.

- That means, the proposer offering something small and the recipient always accepting is the only NE.

Notes:

- We saw that empirically that is not the case.

- Fairness concerns are too strong in that setting.

Coordination Game

- The prediction of play in the Prisoner's Dilemma was easy: both will defect.

- This is the optimal thing to do no matter what the other player does.

- In other games, predictions of play are not so clear.

- One instance is the coordination game.

Coordination Game

A coordination game is a type of static game in which a player will earn a higher payoff when they select the same course of action as another player.

Coordination Game Example

- Choose $L$ or $R$.

- The numbers represent the payoffs a player receives.

- The players only obtain utility if they coordinate their actions.

Notes:

Examples:

- Driving on the right/left side of the road.

- Money adoption.

- Standard adoption.

Coordination Game Example

- The coordination game has two outcomes $(L,L)$ and $(R,R)$ that stand out.

- Clearly, if the other player chooses $L$ ($R$), then it is optimal for the other to do so also.

- So, in the outcomes $(L,L)$ and $(R,R)$ the players choose mutually optimal actions.

Notes:

- That is, for both players it holds:

- Playing $L$ is a best response to the other player playing $L$.

- Playing $R$ is a best response to the other player playing $R$.

Coordination Game Example

- Both $(L,L)$ and $(R,R)$ are instances of Nash equilibrium.

- By their very nature, coordination games always have multiple equilibria.

- The outcome $(D,D)$ in the Prisoner's dilemma is the unique Nash equilibrium.

Notes:

Nash equilibrium: If other players follows the recommended strategy, then the best response for you is to do the same. As the same logic is true for other players, it's reasonable to assume that everybody will indeed follow the recommended strategy.

However, a Nash equilibrium is a weaker notion than a dominant strategy, because if the other players don't follow the recommended strategy, it is not clear what your best response should be.

Equilibrium selection

- So, which outcome does the theory of Nash equilibrium predict in the coordination game?

- None? Both?

- Sometimes people switch between equilibria (if they are made to)...

Sweden, 1967.

Notes:

- The NE does not predict any outcome.

- Sweden switched from left-side driving to right-side.

Schelling Points

- Nash equilibrium does not predict which strategies the players actually take.

- This is especially pronounced in games with multiple equilibria (e.g., coordination games).

- There are theories that offer insights into which strategies players actually take.

Notes:

- In the 1950s American economist Thomas Schelling ran a couple of informal experiments in which he asked his students (quote on slide)

Schelling Points

If you are to meet a stranger in New York City, but you cannot communicate with the person, then when and where will you choose to meet?

- Literally any point and time is a Nash equilibrium...

- However, most people responded: noon at (the information booth at) Grand Central Terminal.

- Basic idea: in case of multiple equilibria, social norms may help to choose one.

Notes:

- Imagine you are held in prison.

- You and your significant other is asked to guess a number.

- If you both guess the same number, you are set free.

- You have the following options: 0.231, 1, or 0.823

- Guessing both the same number is a NE every time.

- It's highly likely you will walk free.

Summary (so far...)

- Typology of games: static/dynamic, complete/incomplete information.

- Three canonical games: Prisoner's Dilemma, Ultimatum-, and Coordination Game.

- The Prisoner's Dilemma has a unique Nash equilibrium, which is dominant, whereas the Coordination game has two Nash equilibria.

- To select among multiple equilibria, the concept of a Schelling Point is sometimes used.

Why are theories of equilibrium important?

- Nash Equilibria are used to predict the behavior of others in a closed system.

- If you can identify a unique Nash Equilibrium or the Schelling point in a system, you have a strong prediction of user behavior.

- So, you can begin to drive user behavior by designing incentives accordingly.

Public Goods

- Non-excludable No-one can be excluded from consumption

- Non-rivalrous My consumption does not affect yours

- e.g., fireworks, street-lighting.

Notes:

- We will now talk about public goods and common goods, which are goods enjoyed by everyone.

- This is, of course, a very important and very tricky class of goods in a collective.

Common Goods

- Non-excludable No-one can be excluded from consumption

- Rivalrous My consumption reduces your possibility to consume

- i.e., a public park, an office coffee machine.

Notes:

- Recall: Public good was non-rivalrous.

Examples:

- Public park: anyone can go; too many people spoil the experience or kills the grass.

- Coffee machine in the office: anyone can use it; too many users may cause congestion or the amount of coffee may be limited.

Public vs.

- Main difference is that in a common good your consumption reduces the value of the good to others.

- This is called a consumption externality that you impose on others (and others impose on you.)

- The tragedy of the commons is that, because you do not take this externality into account, consumption is higher than would be socially optimal.

Stylized Public Good Game:

- $N$ players have 10 US dollars each, say, $N=4$.

- Each player can choose how much to place into a project.

- Funds in the project are magically multiplied by a factor $\alpha$, say, $\alpha=2$.

- Finally, the funds in the project are split equally among all players.

- What would be best for the individual?

- What would be best for the collective?

- As long as $\alpha>1$, it's best for the collective to contribute as much money as possible, because the money in the project increases magically, so we end up with more money that we started with.

- However, the problem is that everyone benefits from the project funds regardless of their individual contribution (it is a common good). If a player decreases their initial contribution by one dollar, their individual payoff decreases by $\alpha/N$ dollars, so as long as $\alpha<N$, it is best for each individual to contribute zero.

- As a result, we can expect that no one will contribute anything, and the money-multiplying powers of the project will be unused. This opportunity cost is a tragedy of the commons.

- Finally, if $\alpha\geq N$ then it would be individually better to contribute everything, and we would not have a tragedy of the commons.

- Fishing gives private benefit but might destroy the broader ecosystem, which has its own value for everyone (e.g., due to tourism).

- Because individual fishermen do not pay for the damage they cause to the broader ecosystem, they will fish too much.

- Producing a good yields private profit but reduces air quality for everyone.

- Because there is no price attached to air quality, the firms do not have to pay for its reduction and, hence, will produce too much.

- There should be fishing/production/mining! After all, there are always benefits to these activities.

- The tragedy of the commons is that the externality is not priced into these activities, driving them to inefficiently high levels.

- Next up class activities.

- Why it might not fail:

- Other incentives:

- Intrinsic motivation

- Reputation concerns (your github history is part of your CV)

- Reciprocity

- Direct benefit: Some contributors also use the software and benefit from improvements.

- Other incentives:

- Need a white board!

- Give Class about 5 minuets to discuss in small groups on this

- Then have 10 minutes to ask the class you solve the 2x2 matrix and discuss (on next slide).

- What is/are the Nash Equilibrium/Equilibria here?

- Which type of games does this remind you of?

- How would you translate this game to real scenarios?

- Game of chicken or Hawk-Dove Game

- "Anti-Coordination Game" with the tension between competition and mutual benefit of compromise.

- Real-world situations of conflict, where both would prefer not to fight but would actually like to intimidate, leading to a real conflict.

- Two businesses would be better off not to engage in price war, but it would be good to be the only one to reduce the price to grab some market share.

- roughly 70 minutes

- We divide the classroom into three groups and play a guessing game.

- The budget for this game is: $250.

- The game is simple: each player enters a number from 1 to 100.

- The player who guessed closest to 2/3 of the average number wins.

- If multiple people win, the payoff is split equally.

- The game is repeated for ten rounds.

- What number did you choose / what was your strategy? (which group were you in?)

- Did your strategy change over time?

- A number above 2/3*100 does not make sense

- If everybody believes that, choosing a number above 2/3*2/3*100 does not make sense

- ... it goes to 0

- But does 0 Win? No!

- Question: Who made these considerations?

- Empirical results:

- Financial Times asked their readers to submit their solution: Winning number was 13 (~1500 participants)

- Other news magazine: ~3700 subjects, winning number 16.99, ~2800 subjects, winning number 14.7

- There were spikes at 33 (response to randomness), 22 (response to that), and 0 (rationality)

- Level-k-thinking: 1 or 2 steps most prevalent, seldom more than that.

- Question: What would be the NE for multiplication of 1 of the mean?

- It becomes a coordination game where all players choose the same value.

- You play a Prisoner's Dilemma (groups of 2) over 10 rounds.

- You will be randomly matched to another student in the class.

- Budget for this game: $500

- You have the option to chat between rounds.

- Important: Keep the chat civil and do not reveal any identifying information about yourself.

- We will read the chat.

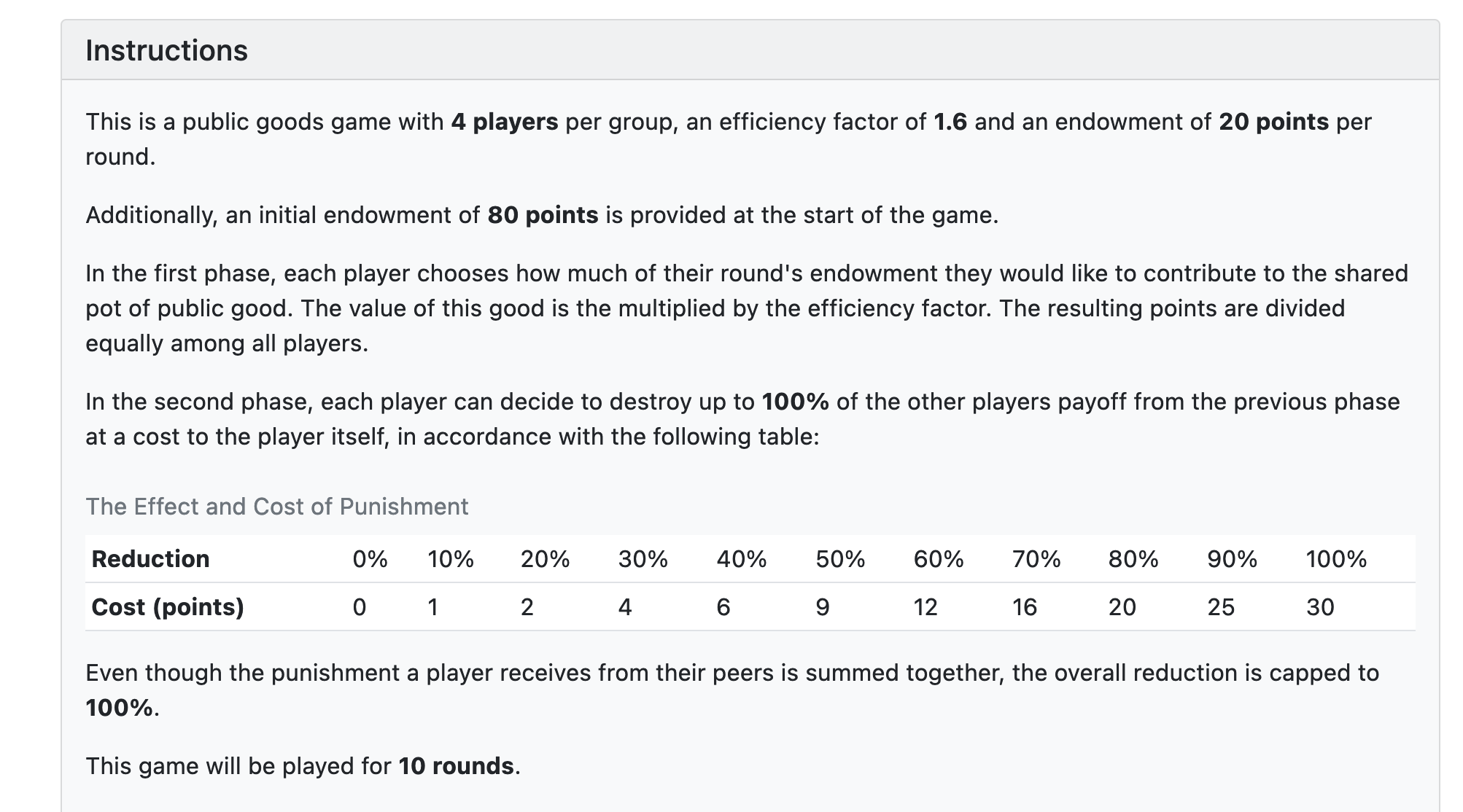

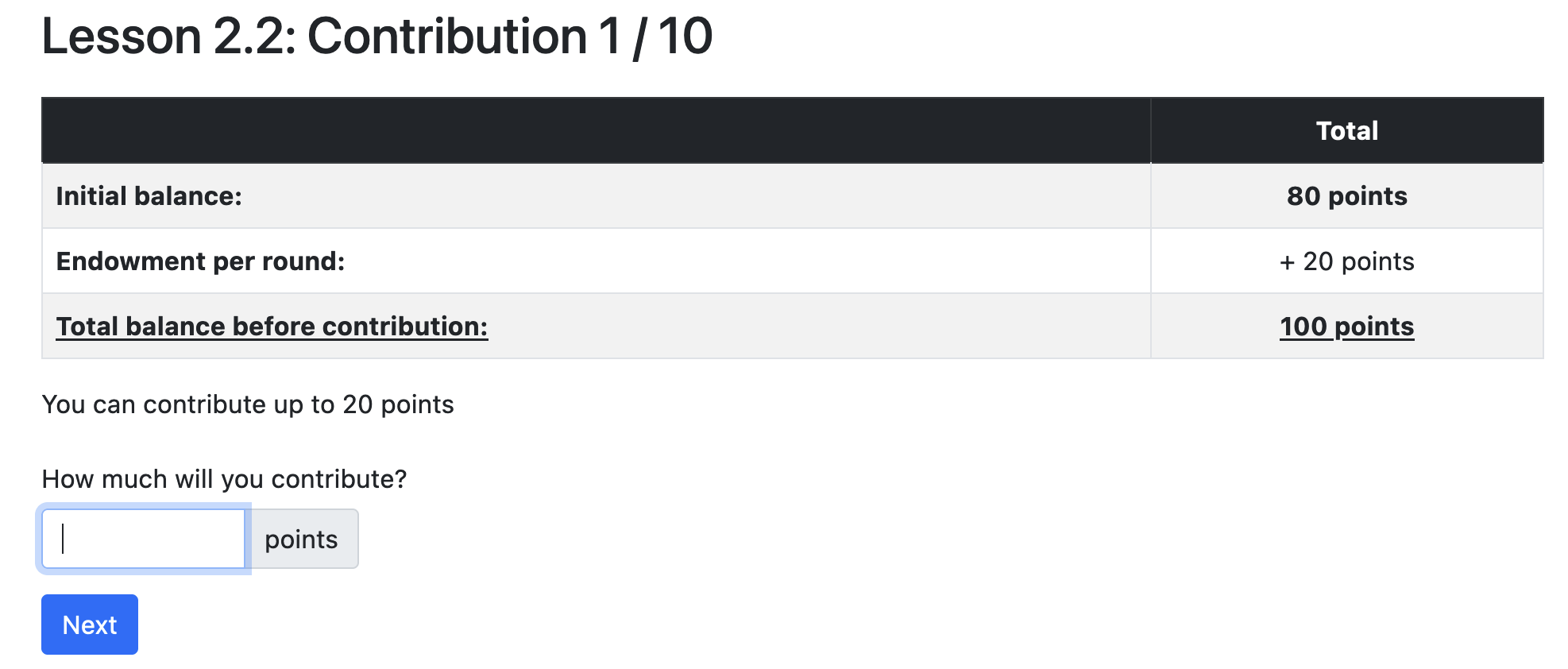

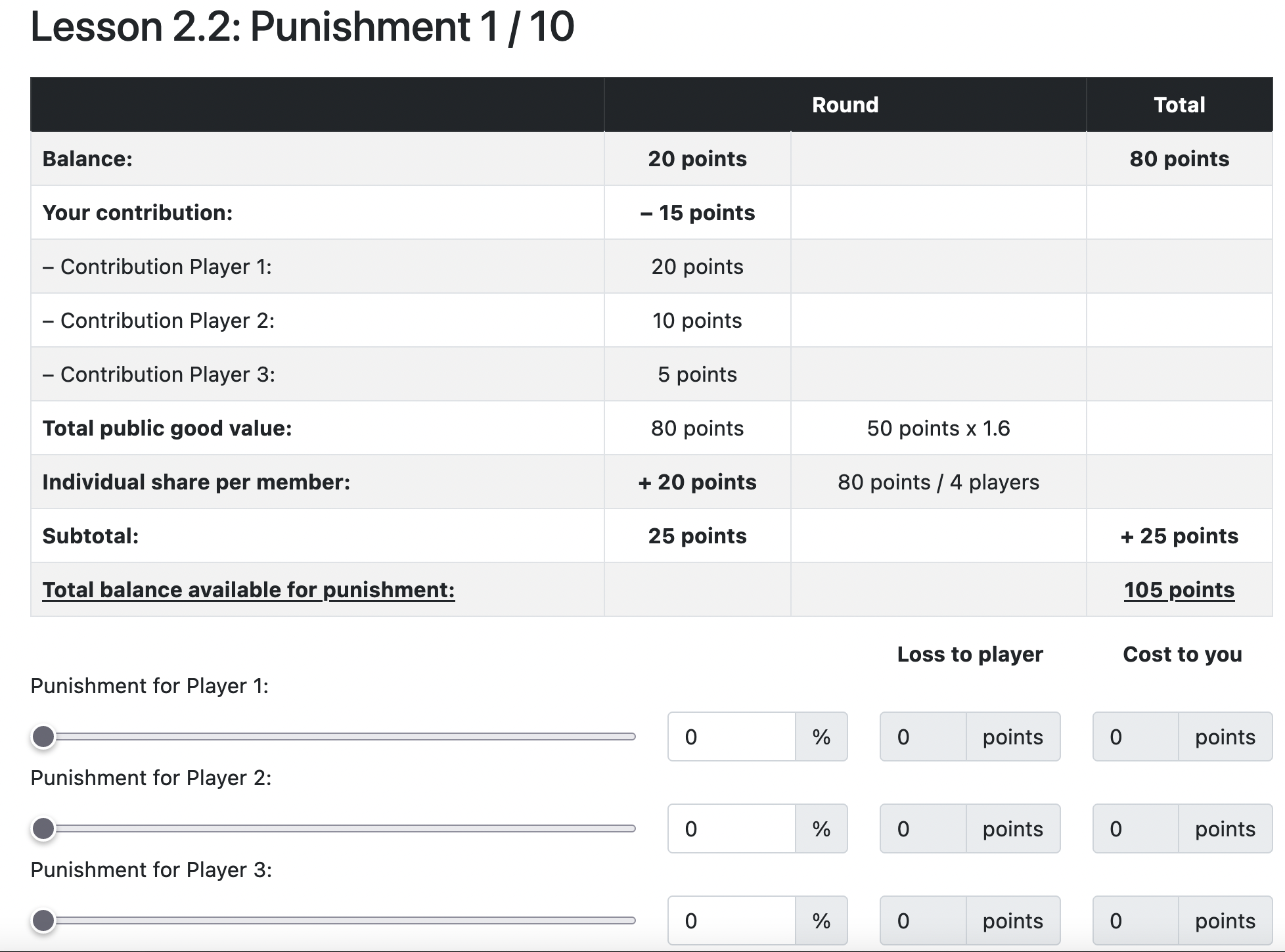

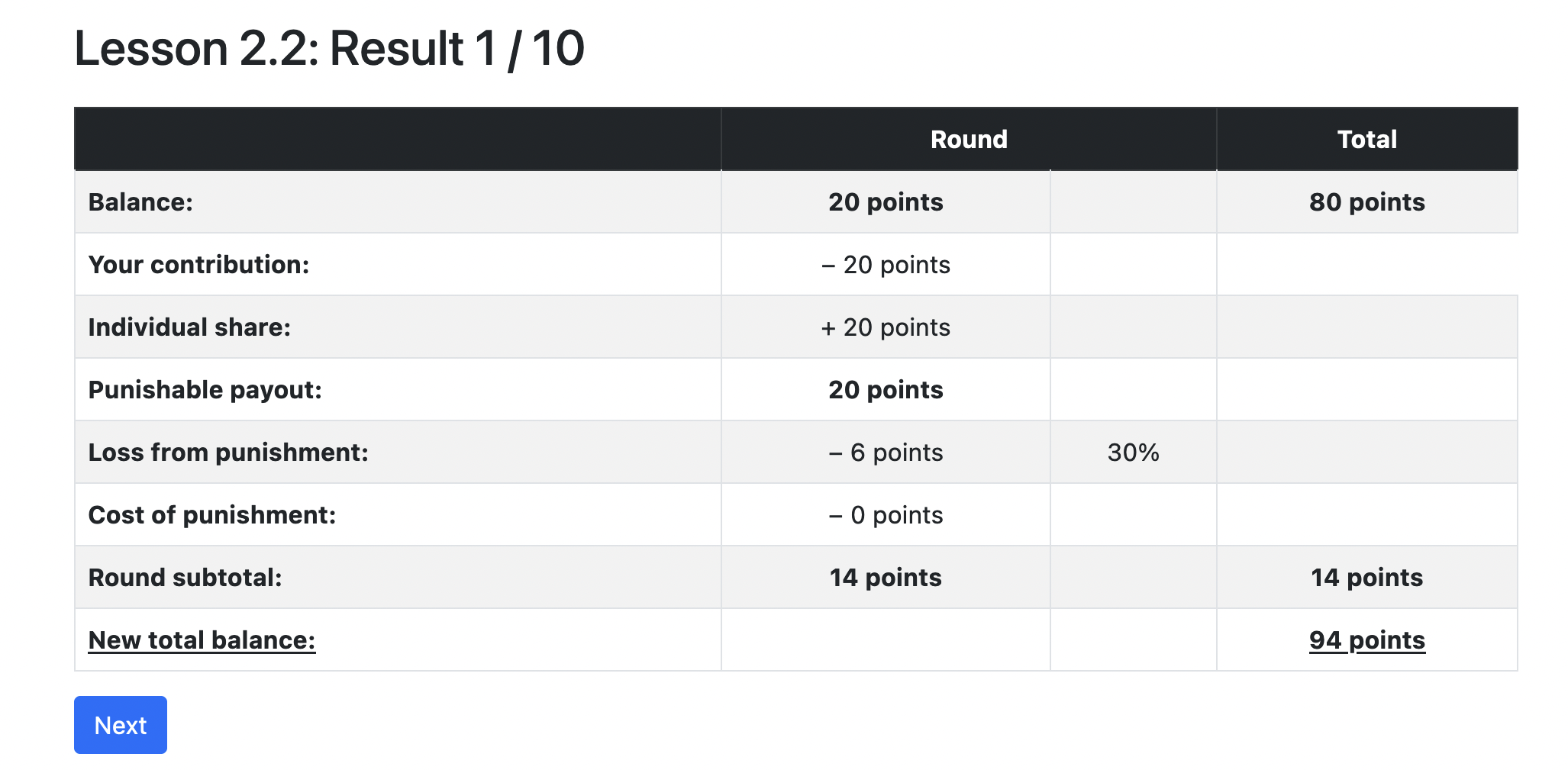

- We will play a public good game as presented in the lesson.

- Budget for this game: $500

- Groups of 4 over 10 periods.

- Money in the project is multiplied by factor $1.6$.

- With one additional mechanism: After each round each player sees the contributions of the other players and can decide to deduct points from them (at own costs).

- What was your strategy?

- Were your groups able to sustain cooperation?

- Did you cooperate?

- Did you punish?

- Additional free rider problem: Punishment was fixed to 100% of the other's points. That means, it was better to hope for other players to punish a player.

- They cooperate maybe because they did not understand the game.

- How could we characterize players to types?

- Freerider

- Cooperators

- Altruists

- What do you think happens when playing this ...

- ... for one round?

- ... for many rounds?

- ... when allowing for communication?

- ... with different group sizes?

- One Round: Little contribution.

- Many Rounds: Some little contribution but quickly to 0.

- Some longer and stronger contribution but eventually going to 0 quickly

- Different group sizes: Larger groups are more prone to freeriding, i.e., cooperation collapses more quickly.

- Question: How can we distinguish freerider from those that only freeride because they expect others to freeride?

- Answer: Ask them to provide a "conditional cooperation table" - i.e., they should state how much they contribute given other's /(average) contributions.

- Real freeriders have 0 even if others contribute.

- the basics of game theoretic concepts.

- different types of games.

- how games can be modeled.

- how to apply game theoretic thinking in our decision making in certain games.

Notes:

Overfishing

Air pollution

But...

Notes:

To be precise, in the last example the so-called "tragedy" is not that producing a good leads to air pollution; after all, this may be unavoidable if we want to consume the good. The tragedy is that even if we agree on the level of production and air pollution that is economically ideal for the collective, we will end up with more pollution.

Break (10 minutes)

Notes:

Open Source

Providing open-source software is like contributing to a public good and the community will therefore sooner or later collapse!

Notes:

Design a 2x2 game

Jack and Christine are rivals and keep taunting each other in front of others. At one time, Jack challenges Christine to a game of chicken. He proposes that they both get in their cars and drive towards each other on a road. In the middle of the distance between each other, there is a small bridge with a single lane. Whoever swerves away before the bridge chickened out. If both keep straight, there is no way to avoid a strong collision between the two cars. All friends will be present to see the result.

Design this game in a 2x2 matrix and assign payoffs to the different outcomes.

Notes:

Design a 2x2 game

Notes:

Workshop: Games

Notes:

Game 1: Guessing Game

Game 1: Questions?

Don't ask about strategies!

Game 1: Guessing Game

Link will be distributed!

Game 1: Discussion

Notes:

Game 1: Results!

Game 2: Prisoner's Dilemma

Game 2: Payoffs

| The other participant | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | Defect | ||

| You | Cooperate | 200 points, 200 points | 0 points, 300 points |

| Defect | 300 points, 0 points | 100 points, 100 points |

Game 2: Questions?

Game 2: Let's go!

Link will be distributed!

Game 2: Results!

Game 3: Public Good Game

Game 3: Instructions

Game 3: Contribution

Game 3: Punishment

Game 3: Payout

Game 3: Questions?

Game 3: Let's go!

Link will be distributed!

Game 3: Discussion

Notes:

Game 3: Results!

Game 3: Discussion

Notes:

What about empirical evidence?