What is Shared Security?

How to use the slides - Full screen (new tab)

What is Shared Security?

On the surface...

Shared Security is an Economic Scaling Solution for Blockchains.

But that is just an answer that sits at the surface. The topic goes much deeper than that.

Let’s explore…

What is Security?

Nearly every attack to a blockchain falls into one of these two buckets:

- Technical Security (cryptography)

- Economic Security (game theory + economics)

We will focus on Economic Security.

Economic Security is represented by the economic cost to change the canonical history of a blockchain.

Chains with higher security are more resilient to malicious activity, like a double spend attack.

Note that a double spend is not inherently an attack!

It is perfectly allowed in all blockchain protocols to sign and submit two messages which conflict with one another.

It is up to the blockchain to come to consensus as to which of these two transactions is canonical.

What does an attack look like?

In this example, someone is explicitly taking advantage of fragmentation in the network to try and create two different canonical chains.

What happens after the attack?

Eventually, the network fragmentation will resolve, and consensus messages will allow us to prove that the malicious nodes equivocated.

That is, they signed messages that validated two conflicting chains.

What is the economic cost?

This will result in slashing the malicious nodes, which should be economically large enough to deter these kinds of malicious activities from occurring.

So Economics and Security are tightly coupled in Blockchains.

The Bootstrapping Problem

What is the Bootstrapping Problem?

The bootstrapping problem is the struggle that new chains face to keep their chain secure, when their token economics are not yet sufficient or stable.

Arguably, the scarcest resource in blockchain is economic security - there simply is not enough to go around.

New Chains Have Small Market Cap

New Chains Are More Speculative

How do we solve this problem?

Shared Security

Different Forms of "Shared Security" Today

- Native: Native shared security is implemented at the protocol level, and is represented as a Layer 0 blockchain, working underneath Layer 1 chains.

- Rollups: Optimistic and Zero-Knowledge Rollups use a settlement layer to provide security and finality to their transactions.

- Re-Staking: Some protocols allow the use of already staked tokens to secure another network, usually through the creation of a derivative token.

but these different forms are not equal…

Deep Dive Into Polkadot Shared Security

Polkadot’s Shared Security

Polkadot is unique in that it provides all connected parachains with the same security guarantees as the Relay Chain itself.

This is native to the protocol, and one of its core functionalities.

Building Blocks of Shared Security

- Execution Meta-Protocol

- Coordination / Validation

- Security Hub / Settlement Layer

- Wasm

- Parachains Protocol

- Relay Chain

Wasm

You can't overemphasize Wasm

In the Polkadot ecosystem, each chain has their state transition function represented by a Wasm blob which is stored on the blockchain itself.

This has many implications, which we have covered, but the key point in this context is that it is very easy to share, generic, and safe to execute.

Game Console Analogy

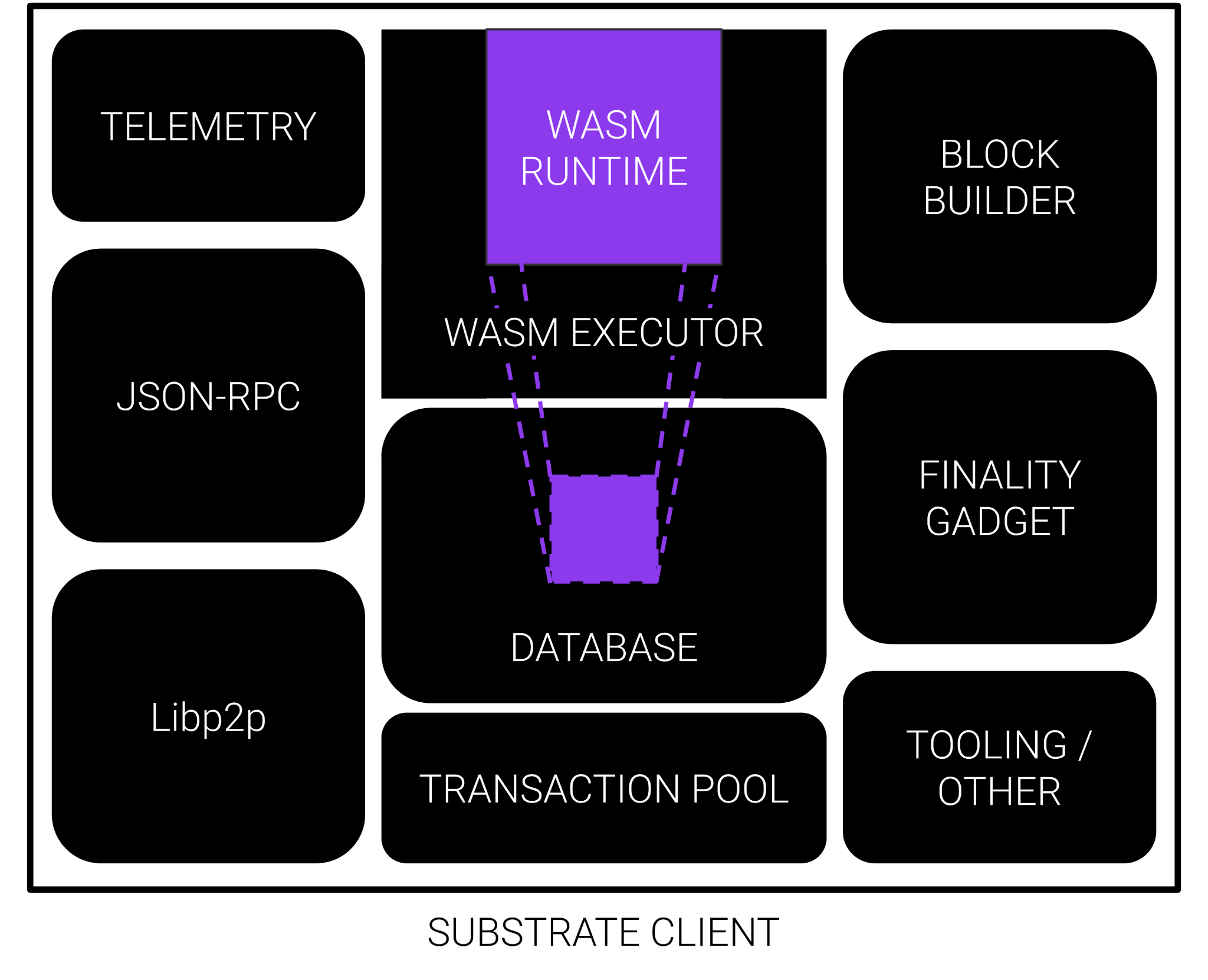

Basic Substrate Client

Wasm Runtimes

A Polkadot Validator Node

In short...

- As you have learned, the Polkadot Client is basically a Wasm executor.

- All of the chains in our ecosystem use Wasm for their state transition function.

- The Wasm meta-protocol allows Polkadot to execute any chain on the fly!

Note that we ACTUALLY EXECUTE the blocks of other chains.

Less trust, more truth!

Parachain Validation

Maximizing Scaling

A scalable proof of stake system is one where:

- security is as shared as possible

- execution is as sharded as possible

Notes:

You should not confuse shared security with sharded security.

a.k.a. cosmos is a sharded security network.

Execution Sharding

Execution Sharding is the process of distributing blockchain execution responsibilities across a validator set.

In Polkadot, all validators execute every relay chain block, but only a subset execute each parachain block.

This enables Polkadot to scale.

How to validate a block?

Submitting Parachain Blocks

Parachains submit new blocks with a proof-of-validity to the network.

Wasm Runtime and latest state root for Parachains already stored on the relay chain.

Parachains Protocol has new blocks that it needs to validate and include.

Polkadot Validators

A random subset of validators are assigned to execute the parachain blocks.

The new state root is then committed to the relay chain so the process can repeat.

How do we stop things from going wrong?

- Data Availability

- Polkadot uses erasure encoding across the validators assigned to a parachain to make sure the data needed to validate a block stays available.

- Approval Checking

- Every validator node is running approval checking processes for a random subset of parachain blocks in every relay chain block. If the initially assigned approvers for a parablock "no-show", then we assume an attack and in the worst case escalate to have the entire validator set check the block.

- Disputes Handling

- When someone disputes the validity of a parablock, all validators must then check the block and cast a vote. The validators on the losing side of the dispute are slashed.

The Relay Chain

The Security Hub for Polkadot

The Relay Chain is the anchor for the Polkadot Network.

- Provides a base economic utility token with DOT.

- Provides a group of high quality Validators.

- Stores essential data needed for each parachain.

- Establishes finality for parachain blocks.

Parachain Blocks Get Finalized

Relay chain block producers commit the new state root to the relay chain once the Parachains Protocol has been completed.

Thus, when a relay chain block is finalized all included parachain blocks will also be finalized!

The Parachain state committed on Polkadot is the canonical chain.

Trust-Free Interactions

This also means that finalization on Polkadot implies finalization of all interactions between all parachains at the same height.

So, shared security not only secures the individual chains, but the interactions between chains too.

Building Blocks of Shared Security

- Execution Meta-Protocol

- Coordination / Validation

- Security Hub / Settlement Layer

Other protocols say they are providing shared security... but do they have these key building blocks?

Comparing Options

Re-Staking Solution

Pros

- Seems to be protocol agnostic, and can be “backported” to new and existing chains.

- Smaller / newer chains can rely on more valuable and stable economies.

Cons

- As tokens are continually re-staked, the economic “costs” needed to attack secured chains decreases.

- No real computational verification or protection provided by these systems.

- Seems to ultimately fall back on centralized sources of trust.

Notes:

See the section on "Key Risks and Vulnerabilities" here:

https://consensys.net/blog/cryptoeconomic-research/eigenlayer-a-restaking-primitive/

Generally there are two main attack vectors of EigenLayer. One is that many validators collude to attack a set of middleware services simultaneously. The other is that the protocols that leverage EigenLayer and are built through it may have unintended slashing vulnerabilities and there is a risk of honest nodes getting slashed.

Much of the EigenLayer mechanism relies upon a rebalancing algorithm that takes into account the different validators and their accompanying stake and security capacity and usage. This underpins the success of the protocol. If this rebalancing mechanism fails (e.g. slow to adjust, latency, incorrect parameters) then EigenLayer opens itself up to different attack vectors, particularly around cryptoeconomic security. It essentially replicates the same vulnerabilities that it sought to solve with merge-mining. So attention must be paid to ensuring that the system is accurately updating any outstanding restaked $ETH and that it remains fully collateralized.

Optimistic Rollups

Pros

- Not limited by the complexity of the on-chain VM.

- Can be parallelized.

- They can stuff a lot of data in their STF.

- They can use compiled code native to modern processors.

Cons

- Concerns around centralization and censorship of sequencers.

- Long time to finality due to challenge periods. (could be days)

- Settlement layers could be attacked, interfering with the optimistic rollup protocols.

- Suffers from the same problems allocating blockspace as on-chain transactions.

- On-chain costs to perform the interactive protocol.

- Congestion of the network.

Zero-Knowledge Rollups

Pros

- Honestly, they are pretty great.

- Proven trustlessly.

- Minimal data availability requirements.

- Instant Finality (at high costs).

- Exciting future if recursive proofs work out.

Cons

- Concerns around centralization of sequencers and provers.

- Challenging to write ZK Circuits.

- Turing complete, but usually computationally complex.

- Hard to bound complexity of circuits when building apps.

- Suffers from the same problems allocating blockspace as on-chain transactions.

- On-chain costs to submit and execute proofs on settlement layer.

- Congestion of the network.

Polkadot Native Shared Security

Pros

- Protocol level handling of sharding, shared security, and interoperability.

- Easy to develop STF: Anything that compiles to Wasm.

- Probably the best time to finality, usually under a minute.

- Data availability provided by the existing validators.

- Much less concern of centralization from collators vs sequencers and provers.

Cons

- Certain limitations enforced to keep parachains compatible with the parachains protocol.

- Wasm STF

- No Custom Host Function

- Constrained Execution Environment

- Wasm is unfortunately still 2x slower than native compilation.

- Requires lot of data being provided and available in PoV.