Benchmarking

How to use the slides - Full screen (new tab)

FRAME Benchmarking

Lesson 2

Overview

- Databases

- Our Learnings Throughout Development

- Best Practices and Common Patterns

Databases

RocksDB

A Persistent Key-Value Store for Flash and RAM Storage.

- Keys and values are arbitrary byte arrays.

- Fast for a general database.

See: https://rocksdb.org/.

Big project, can be very tricky to configure properly.

Notes:

(also a big part of substrate compilation time).

ParityDB

An Embedded Persistent Key-Value Store Optimized for Blockchain Applications.

- Keys and values are arbitrary byte arrays.

- Designed for efficiently storing Patricia-Merkle trie nodes.

- Mostly Fixed Size Keys.

- Mostly Small Values.

- Uniform Distribution.

- Optimized for read performance.

Notes:

See: <https://github.com/paritytech/parity-db/issues/82

Main point is that paritydb suit the triedb model. Indeed triedb store encoded key by their hash. So we don't need rocksdb indexing, no need to order data. Parity db index its content by hash of key (by default), which makes access faster (hitting entry of two file generally instead of possibly multiple btree indexing node). Iteration on state value is done over the trie structure: having a KVDB with iteration support isn't needed.

Both rocksdb and paritydb uses "Transactions" as "writes done in batches". We typically run a transaction per block (all in memory before), things are fast (that's probably what you meant). In blockchains, writes are typically performed in large batches, when the new block is imported and must be done atomically. See: https://github.com/paritytech/parity-db

Concurrency does not matter in this, paritydb lock access to single writer (no concurrency). Similarly code strive at being simple and avoid redundant feature: no cache in parity db (there is plenty in substrate).

'Quick commit' : all changes are stored in memory on commit , and actual writing in the WriteAheadLog is done in an asynchronous way.

TODO merge with content from https://github.com/paritytech/parity-db/issues/82

ParityDB: Probing Hash Table

ParityDB is implemented as a probing hash table.

- As opposed to a log-structured merge (LSM) tree.

- Used in Apache AsterixDB, Bigtable, HBase, LevelDB, Apache Accumulo, SQLite4, Tarantool, RocksDB, WiredTiger, Apache Cassandra, InfluxDB, ScyllaDB, etc...

- Because we do not require key ordering or iterations for trie operations.

- This means read performance is constant time, versus $O(\log{n})$.

ParityDB: Fixed Size Value Tables

- Each column stores data in a set of 256 value tables, with 255 tables containing entries of certain size range up to 32 KB limit.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { const SIZES: [u16; SIZE_TIERS - 1] = [ 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 46, 47, 48, 50, 51, 52, 54, 55, 57, 58, 60, 62, 63, 65, 67, 69, 71, 73, 75, 77, 79, 81, 83, 85, 88, 90, 93, 95, 98, 101, 103, 106, 109, 112, 115, 119, 122, 125, 129, 132, 136, 140, 144, 148, 152, 156, 160, 165, 169, 174, 179, 183, 189, 194, 199, 205, 210, 216, 222, 228, 235, 241, 248, 255, 262, 269, 276, 284, 292, 300, 308, 317, 325, 334, 344, 353, 363, 373, 383, 394, 405, 416, 428, 439, 452, 464, 477, 490, 504, 518, 532, 547, 562, 577, 593, 610, 627, 644, 662, 680, 699, 718, 738, 758, 779, 801, 823, 846, 869, 893, 918, 943, 969, 996, 1024, 1052, 1081, 1111, 1142, 1174, 1206, 1239, 1274, 1309, 1345, 1382, 1421, 1460, 1500, 1542, 1584, 1628, 1673, 1720, 1767, 1816, 1866, 1918, 1971, 2025, 2082, 2139, 2198, 2259, 2322, 2386, 2452, 2520, 2589, 2661, 2735, 2810, 2888, 2968, 3050, 3134, 3221, 3310, 3402, 3496, 3593, 3692, 3794, 3899, 4007, 4118, 4232, 4349, 4469, 4593, 4720, 4850, 4984, 5122, 5264, 5410, 5559, 5713, 5871, 6034, 6200, 6372, 6548, 6729, 6916, 7107, 7303, 7506, 7713, 7927, 8146, 8371, 8603, 8841, 9085, 9337, 9595, 9860, 10133, 10413, 10702, 10998, 11302, 11614, 11936, 12266, 12605, 12954, 13312, 13681, 14059, 14448, 14848, 15258, 15681, 16114, 16560, 17018, 17489, 17973, 18470, 18981, 19506, 20046, 20600, 21170, 21756, 22358, 22976, 23612, 24265, 24936, 25626, 26335, 27064, 27812, 28582, 29372, 30185, 31020, 31878, 32760, ]; }

- The last 256th value table size stores entries that are over 32 KB split into multiple parts.

ParityDB: Fixed Size Value Tables

- More than 99% of trie nodes are less than 32kb in size.

- Small values only require 2 reads: One index lookup and one value table lookup.

- Values over 32kb may require multiple value table reads, but these are rare.

- Helps minimize unused disk space.

- For example, if you store a 670 byte value, it won't fit into 662 bucket, but will into 680 bucket, wasting only 10 bytes of space.

Notes:

That fact that most values are small allows us to address each value by its index and have a simple mechanism for reusing the space of deleted values without fragmentation and periodic garbage collection.

ParityDB: Asynchronous Writes

- Parity DB API exposes synchronous functions, but underlying IO is async.

- The

commitfunction adds the database transaction to the write queue, updates the commit overlay, and returns as quickly as possible. - The actual writing happens in the background.

- The commit overlay allows the block import pipeline to start executing the next block while the database is still writing changes for the previous block.

Practical Benchmarks and Considerations

Let's now step away from concepts and talk about cold hard data.

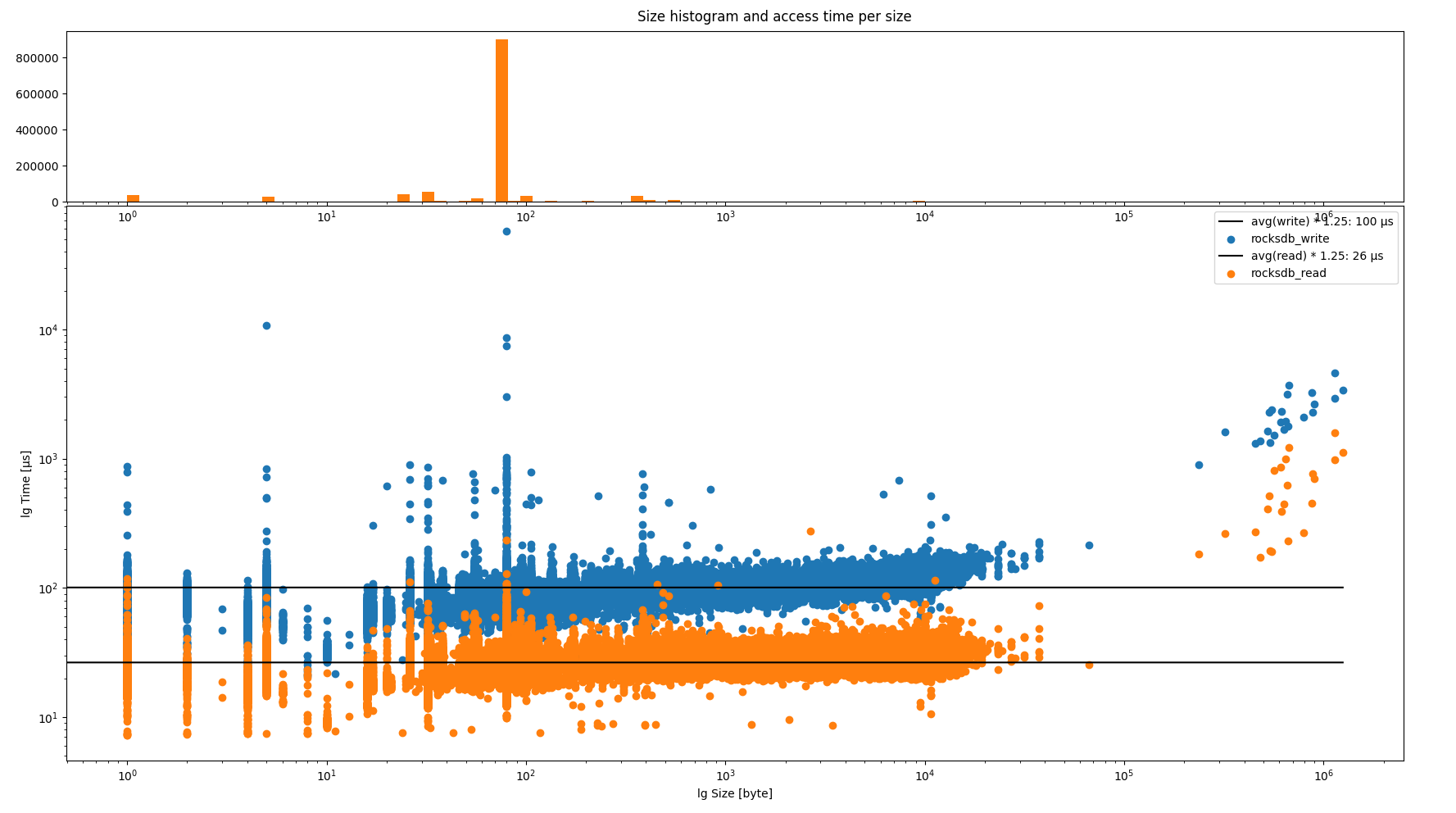

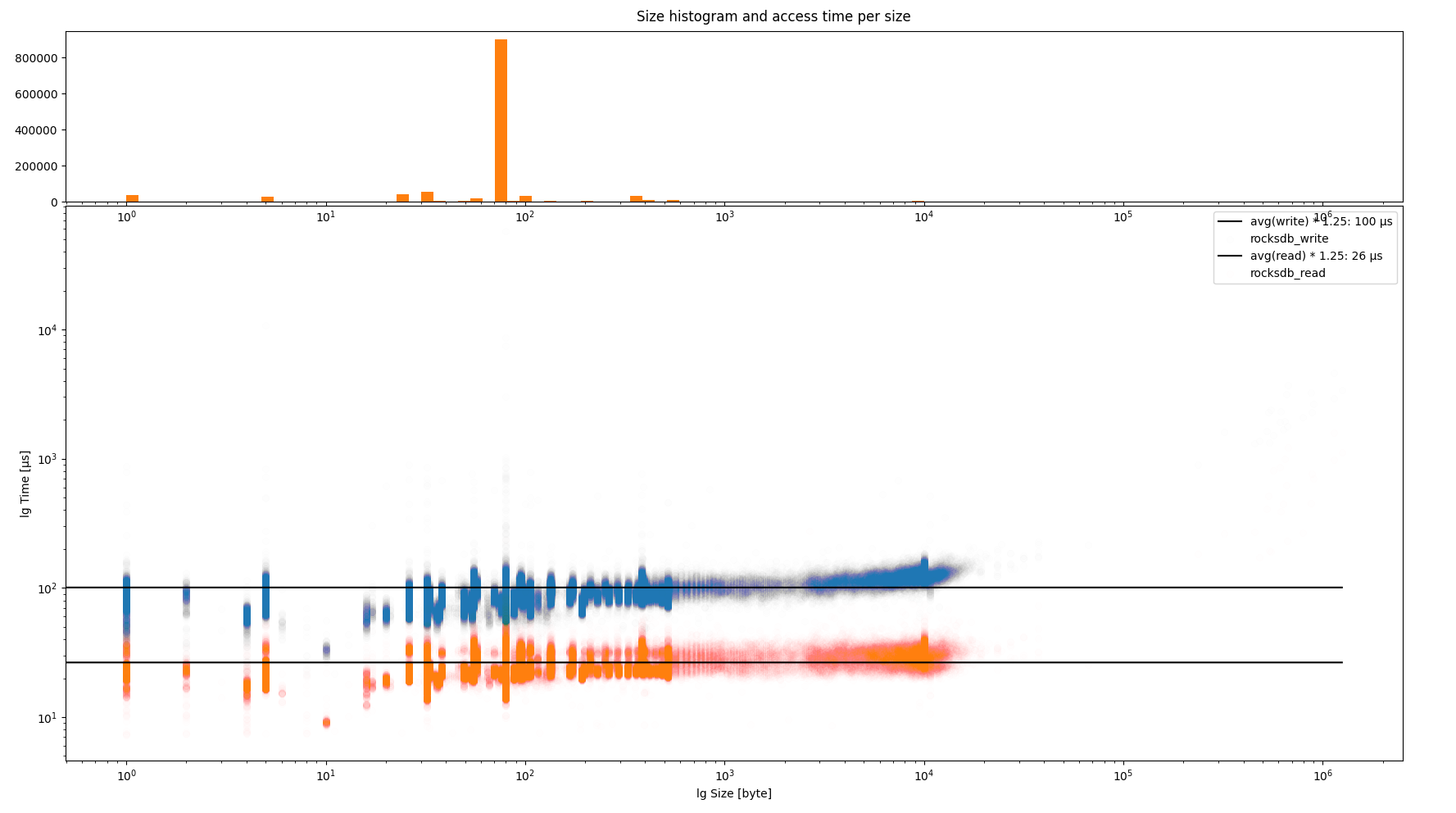

Common Runtime Data Size and Performance

- Most runtime values are 80 bytes, which are user accounts.

- Of course, this would depend on your chain's logic.

Notes:

Impact of keys size is slightly bigger encoded node. Since eth scaling issue, we usually focus on state nodes. Other content access can be interesting to audit enhance though (with paritydb).

See more details here:

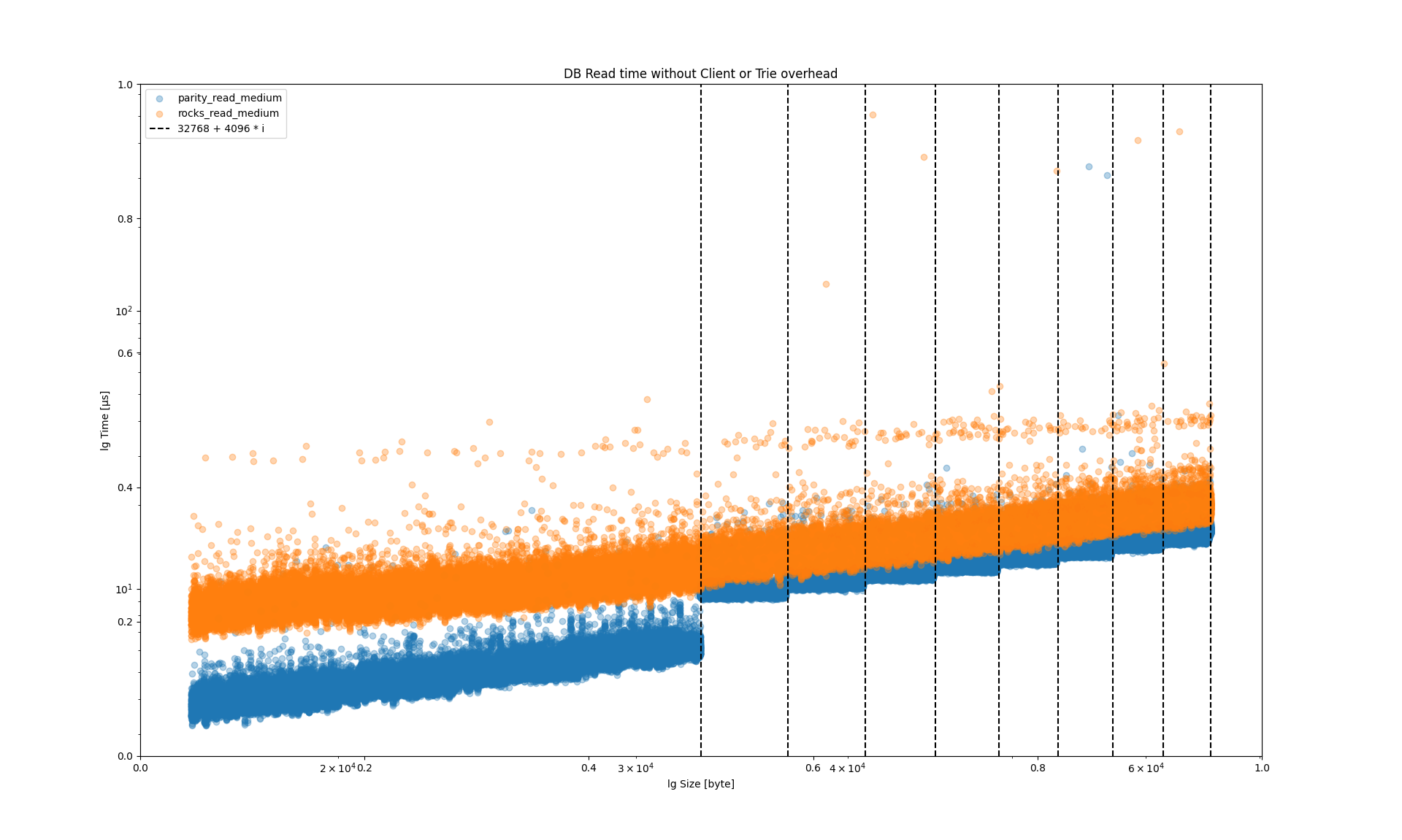

RocksDB vs ParityDB Performance

At 32 KB, performance decreases for each additional 4 KB.

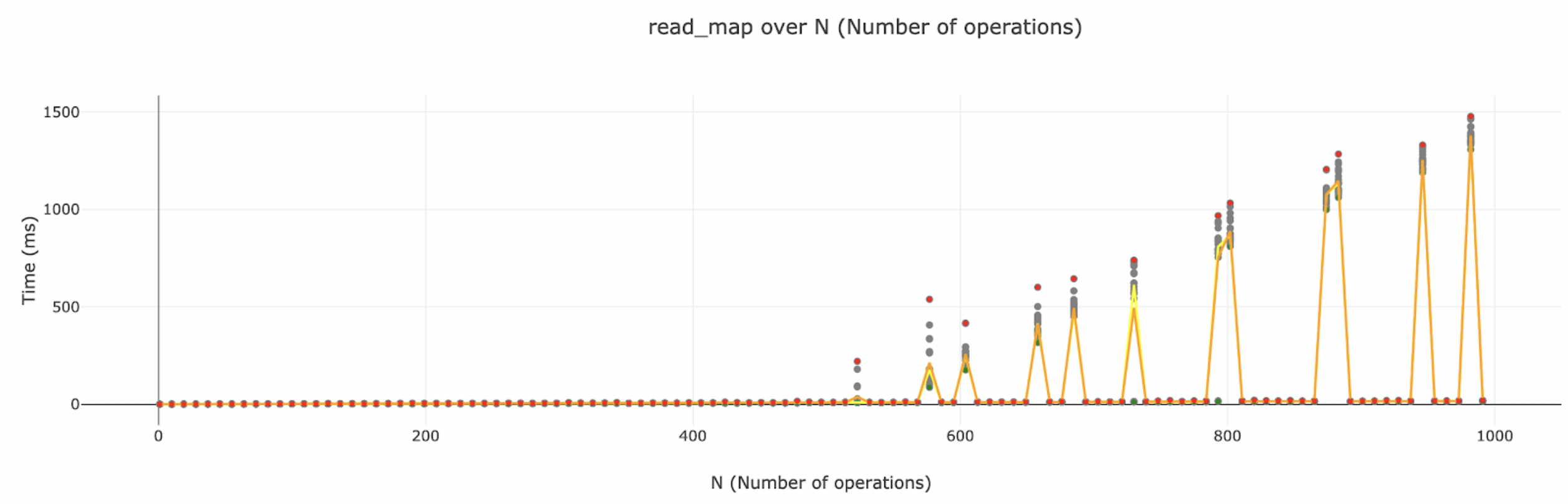

RocksDB Inconsistency

When doing benchmarking, we saw some really bizarre, but reproducible problems with RocksDB.

Things we tried

Things we learned

Isolating DB Benchmarks (PR #5586)

We tried…

To benchmark the entire extrinsic, including the weight of DB operations directly in the benchmark. We wanted to:

- Populate the DB to be “full”

- Flush the DB cache

- Run the benchmark

We learned…

RocksDB was too inconsistent to give reproducible results, and really slow to populate. So we use an in-memory DB for benchmarking.

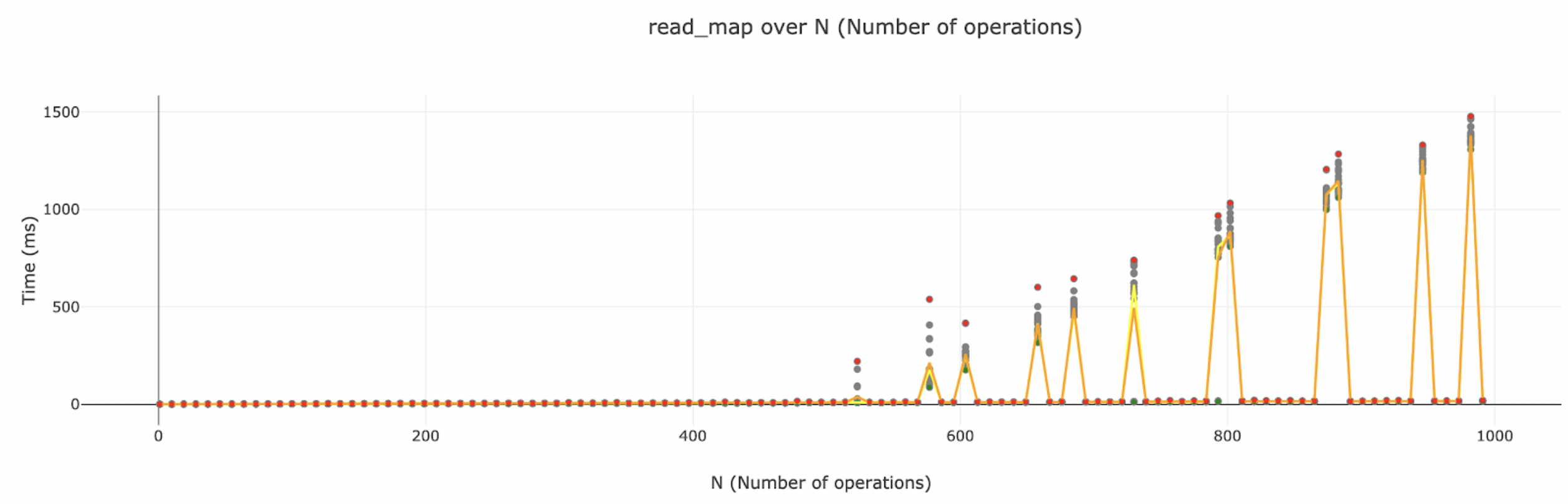

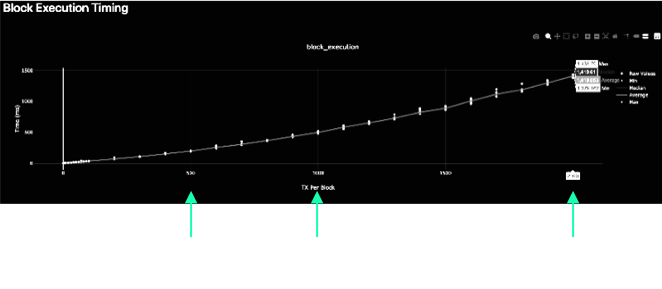

Fixing Nonlinear Events (PR #5795)

We tried…

Executing a whole block, increasing the number of txs in each block. We expected to get linear growth of execution time, but in fact it was superlinear!

We learned…

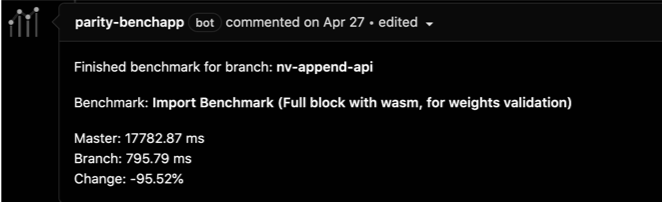

Each time we appended a new event, we were passing the growing event object over the Wasm barrier.

We updated the append api so only new data is pushed.

Enabling Weight Refunds (PR #5584)

We tried…

To assign weights to all extrinsics for the absolute worst case scenario in order to be safe.

In many cases, we cannot know accurately what the weight of the extrinsic will be without reading storage… and this is not allowed!

We learned…

That many extrinsics have a worst case weight much different than their average weight.

So we allow extrinsics to return the actual weight consumed and refund that weight and any weight fees.

Customizable Weight Info (PR #6575)

We tried…

To record weight information and benchmarking results directly in the pallet.

We learned…

This was hard to update, not customizable, and not accurate for custom pallet configurations.

So we moved the weight definition into customizable associated types configured in the runtime trait.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[weight = 45_000_000 + T::DbWeight::get().reads_writes(1,1)] }

turned into...

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[weight = T::WeightInfo::transfer()] }

Inherited Call Weight Syntax (PR #13932)

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[pallet::call(weight(<T as Config>::WeightInfo))] impl<T: Config> Pallet<T> { pub fn create( ... }

Custom Benchmark Returns / Errors (PR #9517)

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { override_benchmark { let b in 1 .. 1000; let caller = account::<T::AccountId>("caller", 0, 0); }: { Err(BenchmarkError::Override( BenchmarkResult { extrinsic_time: 1_234_567_890, reads: 1337, writes: 420, ..Default::default() } ))?; } }

Negative Y Intercept Handling (PR #11806)

Multi-Dimensional Weight (Issue #12176)

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[derive( Encode, Decode, MaxEncodedLen, TypeInfo, Eq, PartialEq, Copy, Clone, RuntimeDebug, Default, )] #[cfg_attr(feature = "serde", derive(Serialize, Deserialize))] pub struct Weight { #[codec(compact)] /// The weight of computational time used based on some reference hardware. ref_time: u64, #[codec(compact)] /// The weight of storage space used by proof of validity. proof_size: u64, } }

Best Practices & Common Patterns

Initial Weight Calculation Must Be Lightweight

- In the TX queue, we need to know the weight to see if it would fit in the block.

- This weight calculation must be lightweight!

- No storage reads!

Example:

- Transfer Base: ~50 µs

- Storage Read: ~25 µs

Set Bounds and Assume the Worst!

- Add a configuration trait that sets an upper bound to some item, and in weights, initially assume this worst case scenario.

- During the extrinsic, find the actual length/size of the item, and refund the weight to be the actual amount used.

Separate Benchmarks Per Logical Path

- It may not be clear which logical path in a function is the “worst case scenario”.

- Create a benchmark for each logical path your function could take.

- Ensure each benchmark is testing the worst case scenario of that path.

Comparison Operators in the Weight Definition

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[pallet::weight( T::WeightInfo::path_a() .max(T::WeightInfo::path_b()) .max(T::WeightInfo::path_c()) )] }

Keep Extrinsics Simple

- The more complex your extrinsic logic, the harder it will be to accurately weigh.

- This leads to larger up-front weights, potentially higher tx fees, and less efficient block packing.

Use Multiple Simple Extrinsics

- Take advantage of UI/UX, batch calls, and similar downstream tools to simplify extrinsic logic.

Example:

- Vote and Close Vote (“last vote”) are separate extrinsics.

Minimize Usage of On Finalize

on_finalizeis the last thing to happen in a block, and must execute for the block to be successful.- Variable weight needs at can lead to overweight blocks.

Transition Logic and Weights to On Initialize

on_initializehappens at the beginning of the block, before extrinsics.- The number of extrinsics can be adjusted to support what is available.

- Weight for

on_finalizeshould be wrapped into on_initialize weight or extrinsic weight.

Understand Limitations of Pallet Hooks

- A powerful feature of Substrate is to allow the runtime configuration to implement pallet configuration traits.

- However, it is easy for this feature to be abused and make benchmarking inaccurate.

Keep Hooks Constant Time

- Example: Balances hook for account creation and account killed.

- Benchmarking has no idea how to properly set up your state to test for any arbitrary hook.

- So you must keep hooks constant time, unless specified by the pallet otherwise.